When you’re in the editing room, do you think about getting into a groove, in a musical sense?

To make it move?

I suppose.

Well, your instinct tells you as you’re doing it. Just like if you’re a standup comic, you’re out there on the floor and your instinct tells you, “Don’t do that next joke like you’d planned, cut right to the one after it.” And so when you’re editing, your instinct says, “Don’t stop for what you thought you were going to show there. Cut it here, you don’t have to show them going back to the apartment, just keep moving.” It’s something that you feel as you go along.

Does it get down to a matter of frames?

Yeah, sometimes it does, particularly with comic stuff, because the slightest thing upsets comedy. I remember when I was making Take the Money and Run. We were cutting on a Moviola. And there was some kind of prison break or something, a lot of confusion, and the editor I was working with at the time, Jim Heckert, said, “Stop where you think the cut should come.” So I was doing it, and I stopped it. We put a mark on the frame and we went on. And when he showed me the scene again, I stopped it and it was on the exact same marked frame, which I didn’t see in advance. Your feeling has to be so true to it that the material demands that this is the place to cut. When it’s comic.

But does it really feel that different when you’re dealing with something more serious, like Match Point?

It’s not as critical. So you run a few seconds longer on something, or a second longer, or shorter—it’s not fatal. But for a joke, you can actually ruin the laugh, and that’s . . . unpleasant.

I can see where it would be. I wanted to ask you a general question about how you work out the movie with your DPs, because you’ve worked with a lot of great ones.

Usually, we have a chat about the film to begin with, and we get on the same page. I like the film, first of all, to be very warm. I don’t like blues, I don’t like sunny days. I like a warm, overcast feeling, I like rain. I don’t like to shoot long days. I like to set up the shot myself, and then let the cameraman look at it. Now, sometimes he’ll say, “Great, it’s beautiful.” And sometimes he’ll say, “It’s very good, I just want to make an adjustment here.” You know, he’ll suggest something that he thinks is better and I’ll usually agree with him because I’m working with guys who are great and they’re usually right and I’m not. Then they light, and we’ve talked about lighting—not of the individual shots, but the overall lighting, and I know their lighting from their other work and from having worked with them before. This is the second film I did with Darius Khondji, we’re gonna do a third this summer. I worked for ten years with Carlo di Palma and 10 years with Gordon Willis, and you get to know them and talk the same language. They’ll never show me dailies that are far off, because they know what I like and they like it. So it works out very well, and there’s never a conflict.

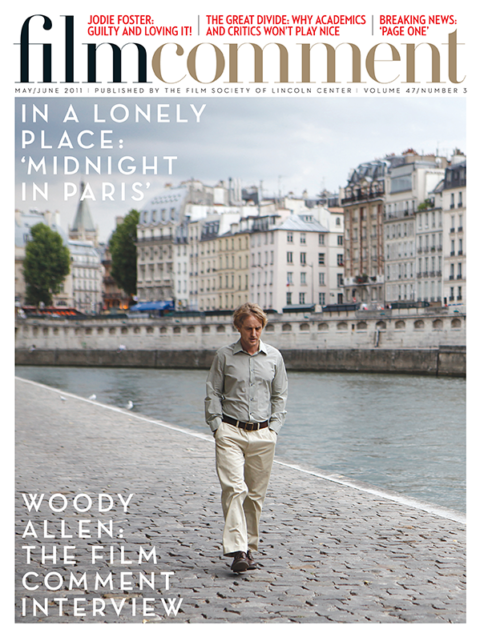

The opening of Midnight in Paris felt very mysterious to me. It’s as if Paris is waiting for someone or something to inhabit it.

Well, I just wanted to put people in the mood of Paris. And Paris is a hard thing to convey because it’s got so much going for it. You know, it’s different in different seasons, in different weather.

I’m sure that it’s going to be compared to the opening of Manhattan, but it’s very different.

It’s different because the opening of Manhattan has dialogue over it. It has a more 1940s, detective story narrative to it. And we started the narrative right away there. Here, we go the entire length of the jazz recording without any dialogue.

The music, by Sidney Bechet, also takes you to an interesting place.

Yeah, because he lived in Paris for so many years, and he wrote that song, and the song feels French. And he’s got that Edith Piaf vibrato in his playing, that real French café singer’s vibrato.

I felt like Owen Wilson brought something very surprising to the movie. Did he surprise you?

Completely surprised me. When I wrote this movie, I did not think of Owen Wilson. The character was an Eastern intellectual, who would have been more Ivy League. If I was younger, I would have played it—not that I’m intellectual, but I look intellectual. And I couldn’t find anybody who was really right who was available and Eastern. And then I was talking with Juliette Taylor and Owen’s name came up. I started to think, “I bet if I rewrote this”—because Owen seemed like a blonde, beachcombing guy with a surf board—“and made it more of a West Coast problem, a West Coast character, he could really do it well.” So I rewrote it, and we sent it to him, and he was eager to play it. And he just . . . I mean, I never had to give him any direction, he knew just what to do, and he played it exactly the way I wanted it.

When he makes the “demented lunatic/right-wing Republican” remark, it seems like he kind of means it.

Yeah. He’s a sweet, sincere guy, and he’s being honest there, thinking, “We’re two Americans, we can disagree and still respect one another.” That’s the Obama fallacy: that your opponent is going to have as much grace and dignity as you have. And they don’t.

I loved the scenes in the Twenties. I loved the ease of them, the re-creations.

We were lucky. We got guys who were able to emulate the original people very well. The guy who looked like Picasso at that time was amazing. I was shocked.

Buñuel was pretty good too.

It was very hard to find a Buñuel. It was a tough one. People know them older. At that young age, Dalí just had that little moustache, and Picasso didn’t have the striped shirt and the bald head.

You’re revisiting something with this movie that you opened up with A Midsummer Night’s Sex Comedy and The Purple Rose of Cairo.

It’s a recurring, nagging feeling of mine that the reality we’re all trapped in is, in actual fact, if you dissect it, like a nightmare. I’m always looking for ways to escape that reality. One escapes it by going to the movies. One escapes it by becoming involved in the trivial nonsense of “Are the Yankees going to win?” or “Are the Mets going to win?” When in fact it means nothing. But life means nothing either. It means as much as the ballgame. So you’re constantly looking for ways to escape from reality. And one of the fallacies that comes up all the time is the Golden Age fallacy, that you’d have been happier at a different time. Just as people think, “If I moved to Paris I’d be happier” or “If I moved to London…” Then they do, and they’re not. Even though these places are great, they’re not happier, because it isn’t the geography that’s eating them up, it’s the existential reality of how grim a predicament we’re in. So, I’ve played around with that before, the notion of wanting to get out of the real world, get out of time. Here, Owen does get a chance to go back, and it’s fine. But he realizes as he looks around that those people want to go back too, and that it doesn’t matter where you go, that life is unsatisfying whether you lived in the renaissance or la belle époque or now or 100 years from now. It’s an unsatisfying situation.

You mean, because it’s never going to be all-embracing, and you’ll never have the perfect conversations and the perfect sympathy that you want.

You’re always looking for some way to beat the house, but you can never do it. You get to Paris in the Twenties, you see that everyone there is unhappy too and they want to be someplace else, and there’s a lot of downside—you go to the dentist and there’s no novocaine, there are a lot of negatives. So you have to eventually conclude that you’re in a meaningless and even tragic predicament. Starting from these grim ground rules, you’ve gotta figure out how you’re going to navigate through life and why it’s worth it. This is all grim stuff for comedy.

I remember when The Magic Lantern was published here and you reviewed it for the Times book review, and you were talking about the monologues in The Passion of Anna. You wrote something like, “It’s great cinema, but it’s also great showbiz.”

Right! That was the thing about Bergman. He was always erroneously thought of as, “Well, this guy’s some kind of cerebral intellectual, I’m not gonna understand this, I’m gonna hate the pictures, they’re black and white, grim theme.” But what made Bergman great—and there were guys who were working the same side of the street but who were not great—was that he was show business, he was an entertainer. When the death figure comes in The Seventh Seal or when those dreams occur in Wild Strawberries, that stuff is very theatrical and very exciting, and you’re on the edge of your seat. The movie’s not homework, where you’re being taught something and you sit through it dutifully. There’s suspense. You know, “My god, what’s gonna happen?”

Bergman deals a lot with magic and the supernatural.

Bergman’s work is full of those kinds of touches. He just does them and assumes you’re gonna go with them. And then you do. They’re done with confidence.

Did you like Saraband?

I did think that he was running out by then. But sure, I liked it, because I had a sentimental feeling for those actors, and I always like what he tries to do. I always feel that his failures are worth more than most people’s successes.

I recently took a fresh look at Another Woman, and I was wondering if Rilke has been important for you.

There’s a conclusion that is arrived at all the time by artists but is frequently unearned—that in the end you have to love, and love is at the core of everything. When it’s not earned by the artist, you pooh-pooh it. But with certain artists, like Rilke, that sense is earned. The sense of “You must change your life” is earned. And that’s what was so overpowering to me about Rilke: fundamentally, love is the best you can do. He was a sufficiently deep enough and great enough poet that when he says it, you feel that he knows what he’s talking about and that he’s not doing it for feel-good purposes. I did that once and regretted it ever since.

On what occasion?

In the original writing of Hannah and Her Sisters, Michael Caine continues to love Hannah’s sister, and he longs for her at those family get-togethers just as much as ever, but he’s grimly attached to Hannah. And my character never gets a really hopeful moment. But I found in the editing that my character’s unhappy moments were unearned, because of my lack of skill, and those endings just fell off the table. They were unhappy in a way that, say, a Chekhov ending is not. In Chekhov, the endings are unhappy but exhilarating. You feel something positive through the unhappiness. I wasn’t a good enough actor to earn that. And so in order to save the movie from utter destruction, I reversed course a little, and it worked, and the picture was very commercially successful. But I always regretted it. I tell myself, “But if I didn’t change it, it would’ve been very unsatisfying to people.” Not simply because it was a sad ending, because sad endings are often not unsatisfying at all, but because I wasn’t skillful enough in the movie to move toward that ending, so that it became the inevitable, the correct ending. When Oedipus puts his eyes out, everything is moving in that direction, and it’s just fine. You don’t need him to say, “Well, I realized that life is unpredictable, and I now have learned two things.” But I felt I needed to do that, and I’ve always regretted it. I’ve always counted that as one of my failures—not commercial, but artistic.

Were you going to end the film with Dianne Wiest telling your character that she’s pregnant?

Yes.

Which is not sad.

No, it wasn’t sad, but it didn’t have the Marx Brothers positive moment in it: “Heck, life is pretty awful but there are some oases.” It didn’t have that bullshit in it. Throughout the entire film, he was unable to have a child, and it looked like he couldn’t, but with the right woman, he could. And that was fine. That was, I felt, something that I deserved to be able to say. I didn’t deserve to be able to do the Marx Brothers scene because it was tacked on, and so was Michael Caine adjusting back to Mia. I played around with it a little and . . . sold out.

Those moments really don’t feel like they’re tacked on.

Well, maybe because we did it skillfully, and it wasn’t as egregious as I felt it to be. But as the author, with another intention, I felt it all the time.

Do you feel like you corrected the mistake in another movie?

I’ve tried to never do it again. Hannah was a big success, but I wasn’t getting the kick out if it that I wanted. If a movie of mine is a success, I like to feel proud and say, “Yes, I worked hard and it came off, and I appreciate that you appreciate it.” But I wasn’t able to have a clear conscience on Hannah.

But the Marx Brothers moment in Hannah and Her Sisters is in keeping with the scene in Manhattan where you’re naming the things that make life worth living. It also seems directly related to the end of Sullivan’s Travels.

Well, I’ll tell you an interesting thing. I only saw Sullivan’s Travels after I made Stardust Memories. I had never been an enormous fan of Preston Sturges.

Were you thinking of Unfaithfully Yours when you shot the scene in the detective’s office in Midnight in Paris?

No, but I did love that movie, because it was Sturges, who was an urbane wit, doing an urbane movie. When he worked with William Demarest and Eddie Bracken and Betty Hutton, it was more bumpkin humor, and I couldn’t warm up to that. I, personally, was a Lubitsch fan, because Lubitsch was cosmopolitan and sophisticated, and unsentimental to the end. And in that one movie, Sturges was cosmopolitan, and I thought it was wonderful. People thought I’d been influenced by Sullivan’s Travels when I did Stardust Memories. Jessica Harper, who was in that movie with me, said, “You have to see Sullivan’s Travels! It’s just like this movie and you’ll love it.” I did see it afterwards and I didn’t love it. But I do think he was a great film director. I thought his pacing was great and he knew how to write. It’s just that I personally was a Lubitsch man. I am a paleface rather than a redskin. I like the European material very much. I respond to it. When you get out toward the middle of the country and the West, I can appreciate things but I don’t enjoy them as much. I’ve often said, not so facetiously, that when I was a kid and a film began with a pan of the New York skyline, I was right with ’em. But when they were rural, I could appreciate the movies, but I had trouble personally enjoying them. I still do.

So I’m assuming that you think the end of Sullivan’s Travels is unearned as well.

Yes, it’s a commercial cop out, because life does not have an ending or a resolution. It’s an unearned optimism.

Do you find yourself looking to movies for inspiration?

Well, it happens automatically. I watch them for pleasure. I don’t study them for the lighting or the camera angles or the blocking. I watch them strictly for the story and for pleasure. And they do influence you. You see good movies and you want to make a movie like that sometime, because it was so much fun and you got such a kick out of watching it. [Door opens] Oh, it’s time for my band practice. [Points] That’s my clarinet. I have to practice every day in order to be mediocre.